Comic Books and Stereotypes

The essence of any narrative is to create characters and situations that allow you to quickly identify the protagonists of a story and illustrate a point. The great fictional characters, such as Antigone, Don Juan and Luke Skywalker materialise stereotypes which structure the imagination, thus perpetuating ancestral prejudices that are transposed in our daily life and which weigh on social relations. While the era is fighting discrimination including racism, sexism, homophobia. We might wonder to what extent the comic book, itself a great producer of stereotypes especially in Belgium and France, promotes or on the contrary deconstructs their perpetuation?

Gender Stereotypes in Comic Books

For almost 180 years that comics have existed, male heroes have played the main role for the most part.

It is clear that in the crowd of comic strip characters, female figures remain a minority and very often linked to typical stereotypes: women have their place in comic books … alongside the hero, ready to support him or treat him in case of a blow. Before the 60s, female characters were only mothers, wives or servants (even witches). From the end of the 1970s, several events took place which contributed to changing the representations of women in adult French-speaking comics (first authors, female stars, feminist messages in graphic novels), but it seems that this inflection was later in youth comics. Currently, the heroines have acquired a leading role, including in children’s works, and there are some militant publishers (such as Gulf Stream and his series Rouge Tagada), as we could meet militant authors among the big names in the adult graphic novel of the 70s and 80s.

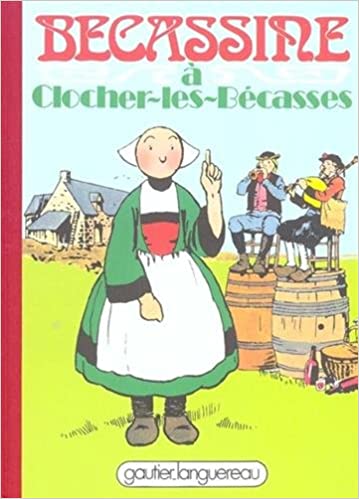

Becassine is a French comic book, which appears for the first time in the first issue of the weekly magazine for young girls “La Semaine de Suzette” in 1905. The character of this Breton maid remains today associated with a negative stereotype of woman as a young foolish or naive girl. The absence of her mouth is easily read as symptomatic of her condition as a woman in the patriarchal system of the comic book.

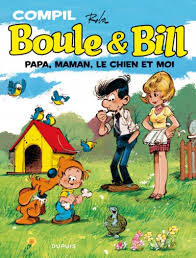

Let’s analyse the characters of Boule’s mother in the Belgian series Boule et Bill and Bonemine in the French comic series Astérix le Gaulois both created in 1959.

Bonemine and Boule’s mother are both secondary characters in their respective series, they are housewives who devote themselves entirely to the maintenance of the marital and family home. They are decked out in their indispensable and unbeatable apron and constantly busy with various domestic tasks. The family home having become their only framework of life, they leave it only very rarely: any leisure would be seen as idleness and their rare “escapades” are generally useful like shopping, with the example of Bonemine who goes to the fishmonger. With their respective husbands, they form the typical couples of the 50s society. They have perfectly integrated the social role that belongs to each of them because of their gender: Abraracourcix (Bonemine’s husband), because of its status of chef, is very influence the public sphere; Boule’s father enjoys a professional activity and presents himself as a model of success and a vector of knowledge. These two men hardly ever take part in household chores, except for Boule’s father who, on rare occasions, gets down to certain jobs but all the same rather reserved for men like DIY. In the Boule and Bill series, if all the duties relating to health and hygiene are taken care of by the mother, the father takes care of the intellectual and school education of his son. So he takes the time to help him with his homework at school; a job that the mother voluntarily ousted by self-censorship as if she had the impression that she did not have the capacity to do so.

Throughout the series, Boule’s mother makes little mention of her dissatisfaction at being confined to household chores, remaining devoted to the home. She rarely raises her voice against his two men. However, in several gags, her work finds itself devalued by remarks from the father who considers that staying at home and not having to go to the office to work, is equivalent to a quiet day, giving him ample time to prepare the meal, compared to him who has worked hard all day. His behavior is indicative of the prejudices and contempt that domestic work was and still is, work considered invisible. In addition, on numerous occasions, the mother seems to fully assume her alleged “hierarchical inferiority” within the family unit by designating the father by the title of “head of the family” and therefore master of all the decisions that could not be disputed.

As for Bonemine, although she has the steadfastness and character, she does not use this strong personality to gain autonomy. We might even wonder if there is some alienation from domestic chores on his part. Thus, in the history of Asterix at the Olympic Games, published in 1968, while all the men of the village are going to participate in the games in Athens, leaving to the village women who in any case have no place in a sports competition , Bonemine does not intend to take the opportunity to take time off. On the contrary, as the chief’s wife, she decides to set herself up as a perfect model for the Gauls and declares to them that “we will take the opportunity to clean up and put some order in until the rascals come back”.

As a reminder, a perfect wife was expected to keep the home in order to ensure the well-being of her loved ones, implying that she worked hard to accomplish all the necessary tasks. This is evidenced, in particular, by advertisements from the end of the 1940s and 1950s, another iconographic support vector of representations, in which the housewife held a central place. Indeed, the queen of good food and proud magician of the immaculate cleanliness of the home is one of the most charismatic and recurring figures in advertising of this period. The housewife very often appeared radiant thanks to her fashionable household appliances, bringing joy to the home as illustrated, for example, by the brand Seb and her “casserole of happiness”. Another rather revealing slogan among others can be cited, that of the poster of the American firm Kellogg’s for the PEP vitamins: ‘so the harder a wife works, the cuter she looks!’

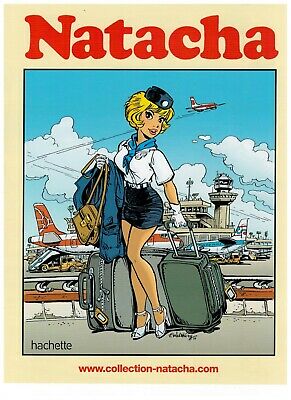

A change comes with the character of Natacha from the series “Natacha, stewardess”, published in February 1970 in Spirou, is a positive heroine: she is intelligent, daring, and independent. She is indeed independent, both psychologically, since we do not see her depend on a male hero to get out of difficult situations or wait for the ideal husband, economically, since she has a job. This work marks an undeniable development in the representation of women in French-language comics since, until then, women were often absent, confined to the household like an insipid mother (Boule and Bill), or limited to subordinate positions such as secretaries, housekeepers, etc. However, Natacha’s profession is also indicative of a certain masculine attitude of male creators, writers and designers. On the one hand, it will be remembered that in the 60s, the profession of flight attendant was both a new profession (mass aircraft for tourists was then recent, but also very quickly feminised and eroticised.

Firstly, care professions such as that of hostess, whose function is to take care of the reception, security and comfort of passengers, are in fact reserved, in fact if not right, only for women in the first decades, when the “management jobs”, like that of piloting, belonged to men. This only extended in the public space the role of women as essentially mothers and / or wives, providers of “care” in the private environment.

In addition, this profession is also quickly eroticised. Indeed, this job of a woman who travels freely in the air will generate or reinforce the male fantasies of slight and fickle woman. Natacha’s qualities are then made ambiguous, comparable to the qualities of superheroines or companions of heroes of American comics. The overbidding that characterises the power of superheroes (and which is even more evident in the era of special effects) seems to produce an “overshoot” for superheroines. Thus, like Wonder Woman or the recent Spider-Woman, they are strong, intelligent and sometimes even independent, but they then have “unreal” bodies and impossible poses; or, as in the case of Lois Lane, they have “normal” bodies, but ultimately remain dependent on “their” man. In the case of Natacha, strategically designed to be suggestive while remaining acceptable), the representation of women depends on the male gaze. Indeed, her “emancipated” side, made of audacity and freedom, only makes her more exciting in terms of adventure and fantasies, the two being intrinsically linked.

In the US, the comics industry has also had a complicated relationship with female characters. They were often hyper-sexualised, unnecessarily brutalised, stereotyped, and used as tokens.

Racial Stereotypes in Comic Books

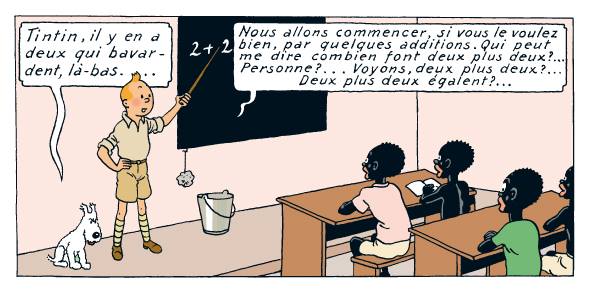

Tintin au Congo is a Belgian coming book created by Hergé in 1931 to encourage young people to leave to colonise Africa. It is clear that Tintin in the Congo develops the colonial stereotypes frequently conveyed towards the indigenous African populations, illustrating the myth of the “good savage” that we find in the famous French advertising image Banania which dates from 1915. Blacks people are considered inferior and display submission to white people in charge of instructing them. Their humanity seems systematically diminished, as evidenced by the language that Hergé attributes to them: they express themselves in approximate and imperfect French.

But it is also on the moral level that these African populations are mistreated. During the scene of the collision with Tintin’s automobile and when it comes to straightening the locomotive, only Snowy gets to work; he asks for help in a rather directive manner “Lazy people” and Tintin adds “You are not ashamed to let this dog work all alone? This is the stereotype of the lazy African man showing through. A few vignettes further on, it is Snowy who tames the lion while the African warriors were afraid of it and fled.

On the contrary, moral qualities and mastery of technical modernity are resolutely on the side of Tintin and the white colonisers. Tintin is courageous in everything he does, both when he dives looking for Snowy who drowns at the start of the story, but also when he goes hunting for lions, or fighting against diamond traffickers. It is ingenious when it uses an electromagnet to draw arrows from these enemies, or when it gets rid of a leopard or an elephant. The work of the colonisers through Tintin and the action of the missionaries are valued.

Tintin does justice like King Solomon in the Bible, by cutting in half a hat that two young Africans were fighting over; he treats a patient with a quinine tablet; he teaches. The action and the benefits attributed to the colonisers are systematically highlighted. With Tintin, the coloniser is magnified, he is the man who brings technical modernity through cinema (Tintin is organising a first screening in an African village), or medicine. The West imposes itself as a colonial power because it is based on an industrial and technical revolution which gives it an obvious strategic advantage: this is also the self-justification of colonialism in Tintin in the Congo.

In short, in Tintin in the Congo the African is presented as a big, lazy and somewhat naive child, saved by the white coloniser who brings medicine, justice, peace between the tribes: this is the whole vision of paternalistic racism inherent to colonialism which is expressed here to define an agreed and consensual vision of colonial action in the interwar period. Africa is presented as a welcoming, exuberant and exotic continent.

Tintin in America pubished in 1932, also feeds stereotypes. “Redskins” who capture Tintin want to scalp him. Native Americans are presented as wild and dangerous.

Lucky Luke a Belgian comic book created in 1947 which tells the adventure of a gunslinger in the American Old West, contained many racial stereotypes. Mexicans are considered lazy and think only of sleeping, African-Americans are portrayed with big lips and everything, and most importantly, Native Americans have the worst treatment, portrayed as stupid, backward, aggressive and belligerent, wanting scalps, unable to make correct sentences like the white characters, living like “savages”, and perpetuating the cliché of the Indians with feathers and teepees (while the native American tribes were not all like that, some lived in hard built houses before the arrival of white people for example).

In the United States, the changes in representation have followed a similar trajectory but that they have been determined by the history of the country. The main changes took place from the end of the Second World War, when the black veterans returned from Europe after having fought under the American flags, and were still facing De Jure segregation in the Southern States. Since then, militant associations like the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) have campaigned against caricatures of African American soldiers in cartoons and comics.

In the mainstream comics, new representations also appeared through the publication of comic books featuring black superheroes like Black Panther (1966) or Luke Cage (1972) which shed light on the experiences of their protagonists under a more social angle. This “revolutionary” trend gradually faded in the 1980s. The late 1990s were much more prolific in this area and an artistic revival was carried by young black press cartoonists – like Aaron McGruder and his comic strip Boondocks created in 1996 – which deal head on with delicate subjects such as racism, the black condition in an America which defines itself as “post-racial”, the role of white and black media in the dissemination of stereotypes etc.

About Doria Adoukè

We are committed to challenging stereotypes and promoting diverse representation, particularly of Black women, in the world of comic books. Explore our black woman comic book featuring dynamic characters, funny and captivating stories.